Youth's Lives Every Day

Key Findings

- Mental health care needs among LGBTQ+ youth extend beyond those with a formal diagnosis: while 89% of diagnosed youth wanted mental health care, 76% of undiagnosed youth also reported wanting mental health care.

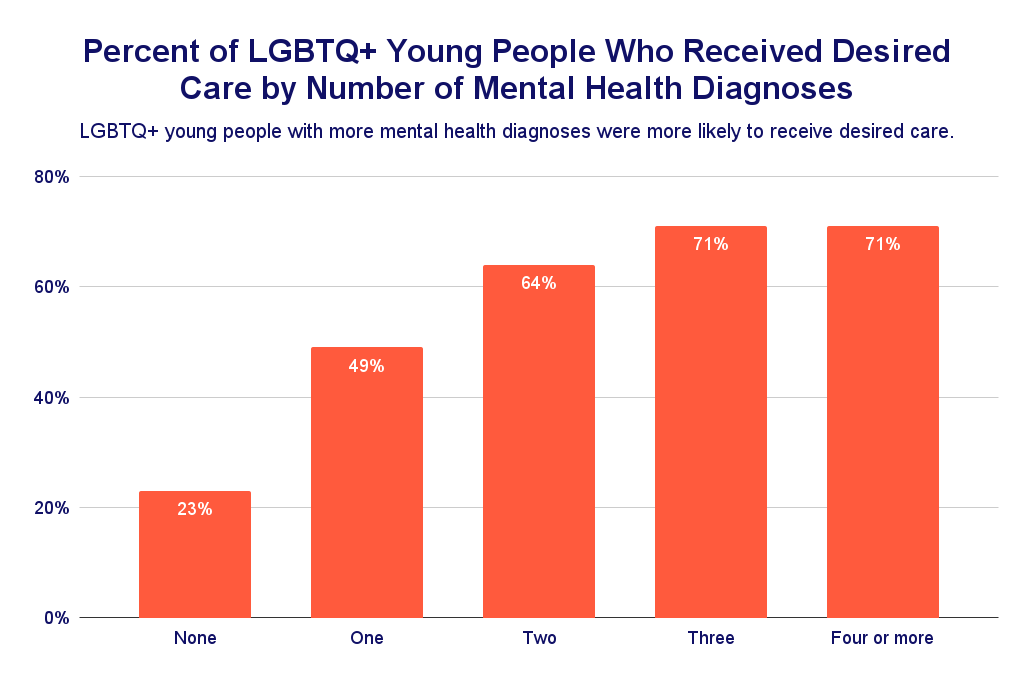

- Individuals with more mental health diagnoses were more likely to report having received desired care: 71% of those with four or more diagnoses reported receiving desired care, compared to just 23% of those without a diagnosis.

- Diagnoses were often comorbid, or co-occurring at the same time, such as having been diagnosed with both an anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.

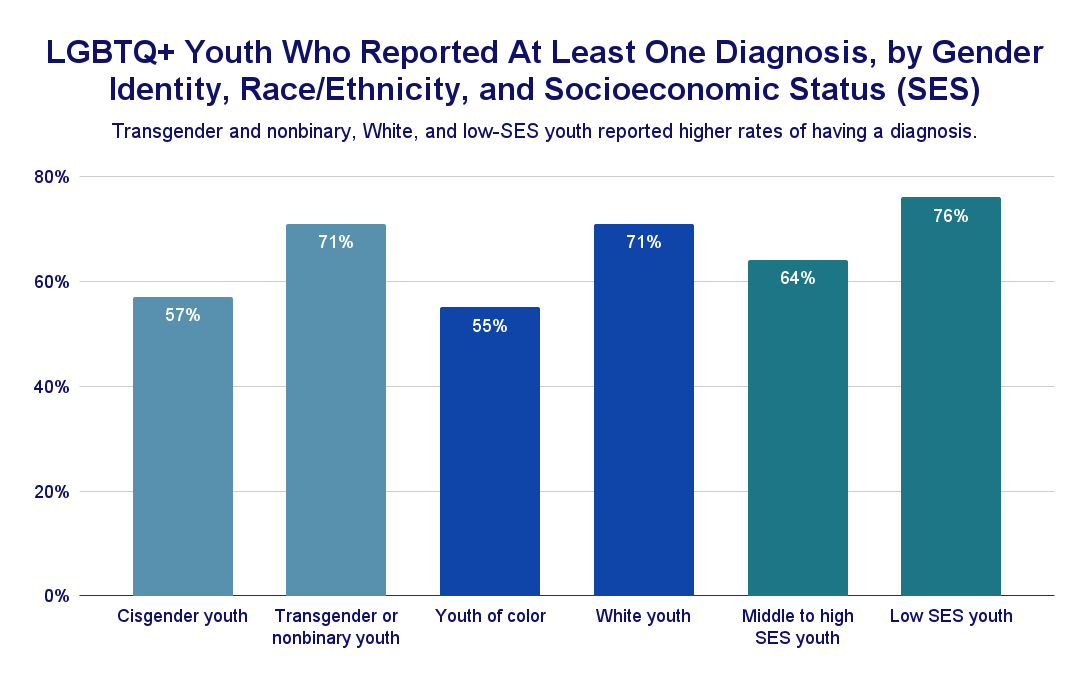

- Transgender and nonbinary youth, White youth, and those unable to meet basic financial needs were more likely to report receiving a mental health diagnosis compared to their cisgender, youth of color, and financially secure peers.

The 2025 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ+ Young People is now open!

If you’re LGBTQ+ and 13–24, we would love to hear from you.

Background

LGBTQ+ young people experience higher rates of mental health challenges compared to their non-LGBTQ+ peers.1,2 While prior studies have examined the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors among LGBTQ+ young people,3 less is known about the prevalence of other conditions or formal mental health diagnoses in this population. Some studies have begun to estimate rates of diagnosed mental health conditions beyond depression and anxiety,4 but research has rarely explored how these diagnoses—and diagnostic comorbidities—impact LGBTQ+ youth’s ability to access mental health care. Additionally, there is limited understanding of how young people with mental health symptoms, but without a formal diagnosis, navigate the mental health care system. Using data from The Trevor Project’s 2024 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ+ Young People, this brief examines patterns in self-reported mental health diagnoses and mental health care access among 18,663 LGBTQ+ youth ages 13 to 24.

Results

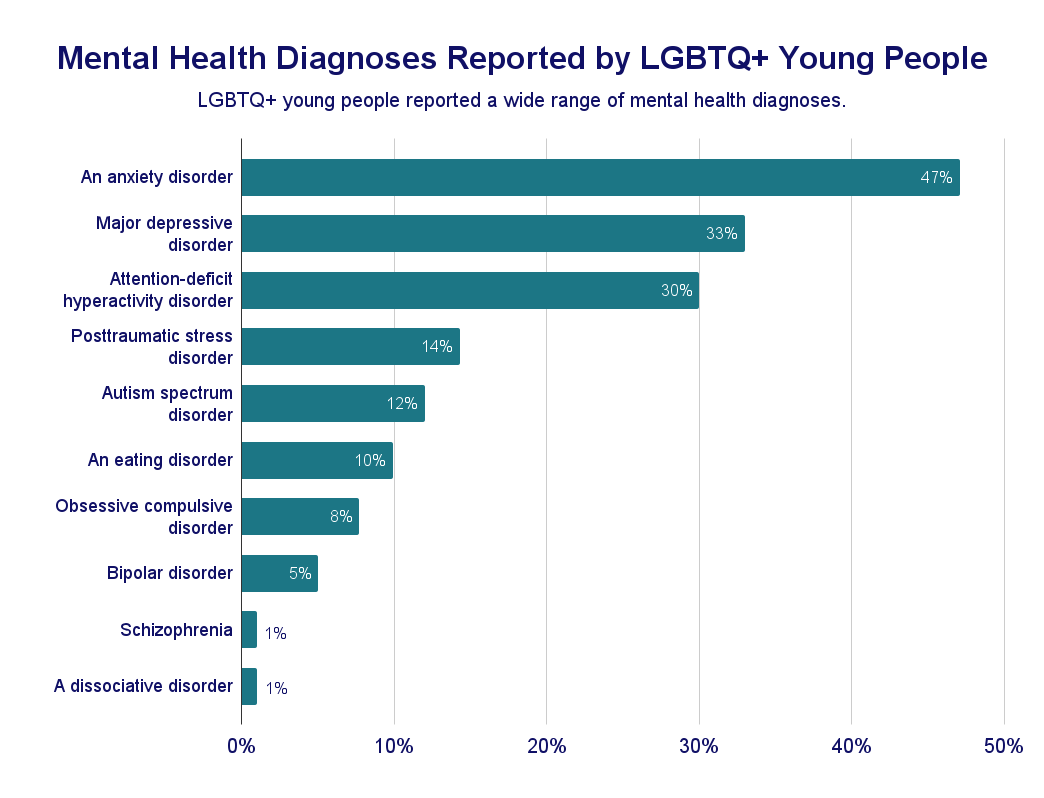

Of the total sample, nearly two-thirds (65%) reported having received at least one mental health diagnosis in the past, while 35% reported none. The most commonly reported diagnoses were an anxiety disorder (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder; 47%), major depressive disorder (MDD; 33%), and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; 30%). Some of the less commonly reported diagnoses included bipolar disorder (5%), schizophrenia (1%), and a dissociative disorder (e.g., dissociative identity disorder; 1%).

We examined participants’ cumulative number of mental health diagnoses (range = 0-10; median = 1; mean = 1.61, standard deviation = 1.69). LGBTQ+ young people who reported more diagnoses also reported higher rates of receiving desired care in the past year. For example, 71% of participants with four or more diagnoses reported receiving desired care, compared to just 23% of those with no diagnosis and 49% of those with one diagnosis, despite both of these groups also desiring care. Notably, although 89% of LGBTQ+ young people with a mental health diagnosis wanted mental health care, the majority without a diagnosis (76%) wanted mental health care as well.

Mental health diagnoses were frequently related to one another. Some diagnoses were comorbid, overlapping more frequently than others. For example, a substantial overlap was observed between MDD and anxiety disorder, with 85% of participants with an anxiety disorder also reporting a diagnosis of MDD. Additionally, among the 14% of LGBTQ+ young people who had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 70% also had MDD and 83% had an anxiety disorder. In contrast, among those without a PTSD diagnosis, 27% had MDD and 41% had an anxiety disorder.

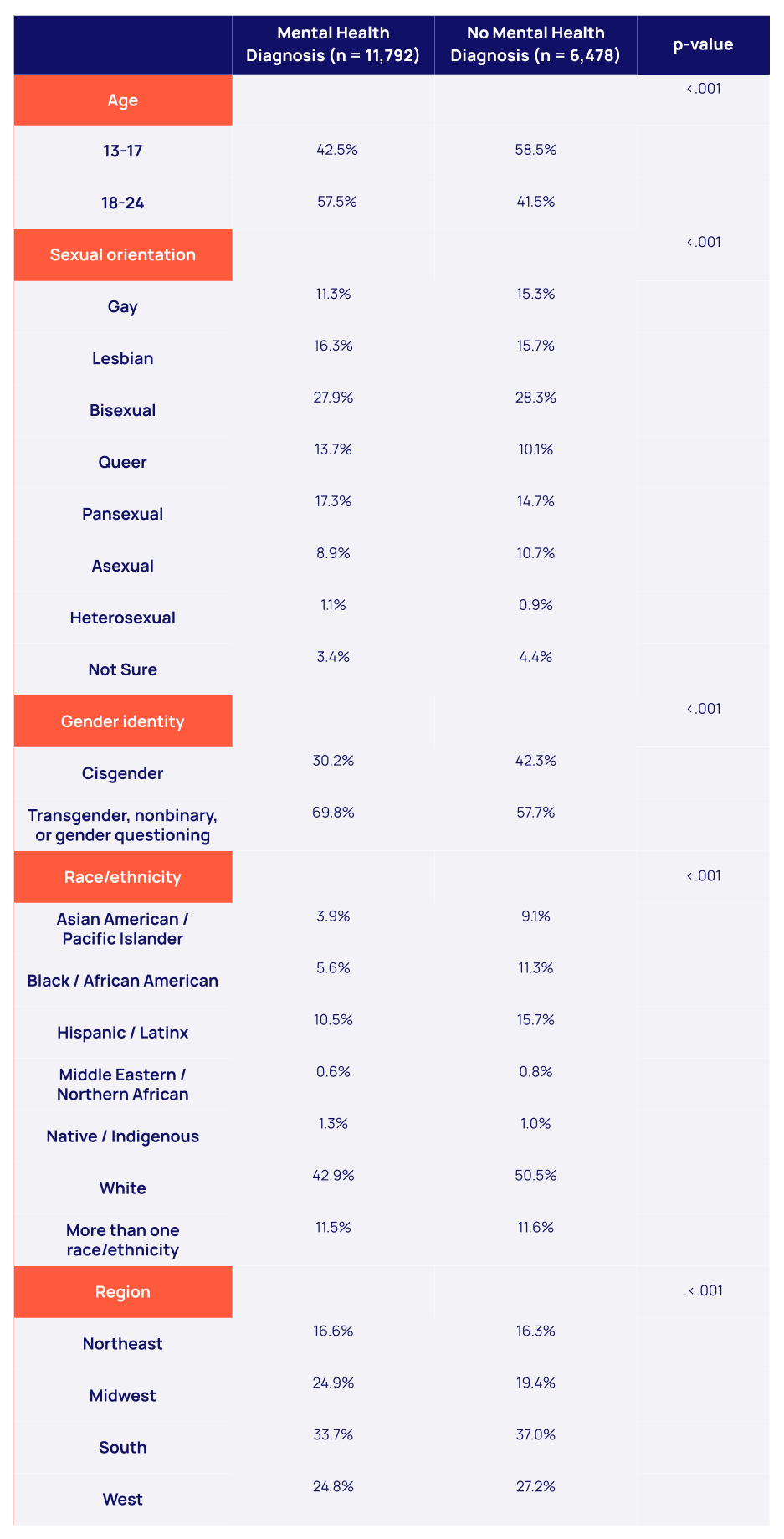

Underlying these findings are demographic disparities. Transgender or nonbinary young people were more likely to report a diagnosis (71%) than gender-questioning (61%) or cisgender youth (57%). Youth who were White were more likely to report having received a diagnosis compared to youth of color (71% vs. 55%). Additionally, youth who were unable to meet basic financial needs were more likely to report having a diagnosis compared to those whose basic needs were met (76% vs. 64%).

Looking Ahead

These findings highlight the substantial mental health needs among LGBTQ+ youth, both those with and without a formal diagnosis. While anxiety disorders, MDD, and ADHD were the most commonly reported diagnoses, many young people experienced multiple co-occurring conditions, and nearly a quarter of those with a diagnosis reported having four or more conditions. Encouragingly, youth with more diagnoses were more likely to report receiving the care they wanted—suggesting that those with greater clinical need may be accessing services. However, it is also possible that this reflects disparities in diagnostic access: youth who are already engaged in care may be more likely to receive diagnoses, rather than diagnoses necessarily leading to improved access. In either case, access to care remains limited, even among those who want support.

Over three-quarters of LGBTQ+ youth without a formal mental health diagnosis still reported wanting care. This highlights the importance of recognizing and supporting mental health needs that may not be captured through diagnostic labels, including preventive care or care for symptoms that are not indicative of a diagnosis. Patterns of comorbidity, such as the frequent co-occurrence of anxiety and depression, underscore the complexity of LGBTQ+ youth mental health. These overlapping experiences call for integrated, trauma-informed approaches that account for the ways symptoms can manifest together. They also emphasize the need for affirming providers who are trained to properly diagnose mental health conditions, particularly in LGBTQ+ youth who may present differently than their cisgender and heterosexual peers.4

Disparities by gender identity, race, and socioeconomic status point to the role of structural inequities in both rates of diagnosis and access to care. Transgender and nonbinary youth, as well as those experiencing economic hardship, were more likely to report having received a mental health diagnosis. For these youth, this may reflect more frequent contact with health care systems—particularly due to the medicalization of gender dysphoria—rather than improved access to care.5 At the same time, these patterns highlight how structural factors may both increase mental health risk and shape pathways into diagnosis and care. Still, the pathways into care may differ—reinforcing the need for culturally competent, identity-supportive services that meet youth where they are.

These results emphasize the need to expand access to mental health care that affirms the identities and lived experiences of LGBTQ+ youth. Providers must be equipped to understand the impact of intersecting systems of oppression—such as transphobia and poverty—on young people’s mental health. Future research should continue to explore how comorbid diagnoses, unmet care needs, and social marginalization interact to shape the mental health journeys of LGBTQ+ youth. A deeper understanding of these intersections can inform systems-level interventions that reduce barriers to care, promote early access, and ensure that all youth—diagnosed or not—receive the support they need and deserve. In addition, future research should include more formal evaluation of diagnoses, whenever possible, rather than relying solely on self-report.

The Trevor Project is committed to supporting LGBTQ+ young people through crisis intervention, research, and advocacy initiatives. Our 24/7 crisis services—available by phone, chat, and text—ensure that LGBTQ+ youth can connect with trained counselors whenever they need support, regardless of their mental health diagnosis or presentation. In response to the high rates of comorbid mental health conditions and widespread desire for care—including among youth without formal diagnoses—our services are designed to meet young people where they are in their mental health journey. TrevorSpace, our dedicated social networking platform, provides a safe and welcoming space for LGBTQ+ young people to connect with supportive peers, helping to reduce isolation and promote community support. Our education team equips adults with the tools needed to support LGBTQ+ youth across diverse identities and experiences, including those navigating multiple diagnoses, systemic barriers, and unmet care needs. Meanwhile, our advocacy team works at the state and federal level to promote access to inclusive, supportive environments and affirming mental health care. We remain committed to publishing research that explores the nuanced mental health experiences of LGBTQ+ youth, especially those impacted by structural inequities, to drive informed policy and life-saving intervention.

You can read more related research from The Trevor Project here: Mental Health Care Access and Use among LGBTQ+ Young People, Mental Health and Access to Care for LGBTQ+ Girls and Young Women, and Trauma and Suicide Risk Among LGBTQ Youth. Additionally, The Trevor Project provides resources for both LGBTQ+ young people and their allies, such as LGBTQ+ Mental Health Resources.

Data Tables

Demographic Characteristics of LGBTQ+ Young People with a Mental Health Diagnosis

Methods

References

Recommended Citation

The Trevor Project. (2025). Mental Health Diagnoses and Access to Care Among LGBTQ+ Young People. https://doi.org/10.70226/MTFA6875

For more information please contact: Research@TheTrevorProject.org

© The Trevor Project 2025